Two problems for sophistication

published at Algorithmic Learning Theory 2015 withHow do we quantify information? How do we capture, and formalize the intuition that some objects are rich in information, and some aren’t, even though they may be the same in size?

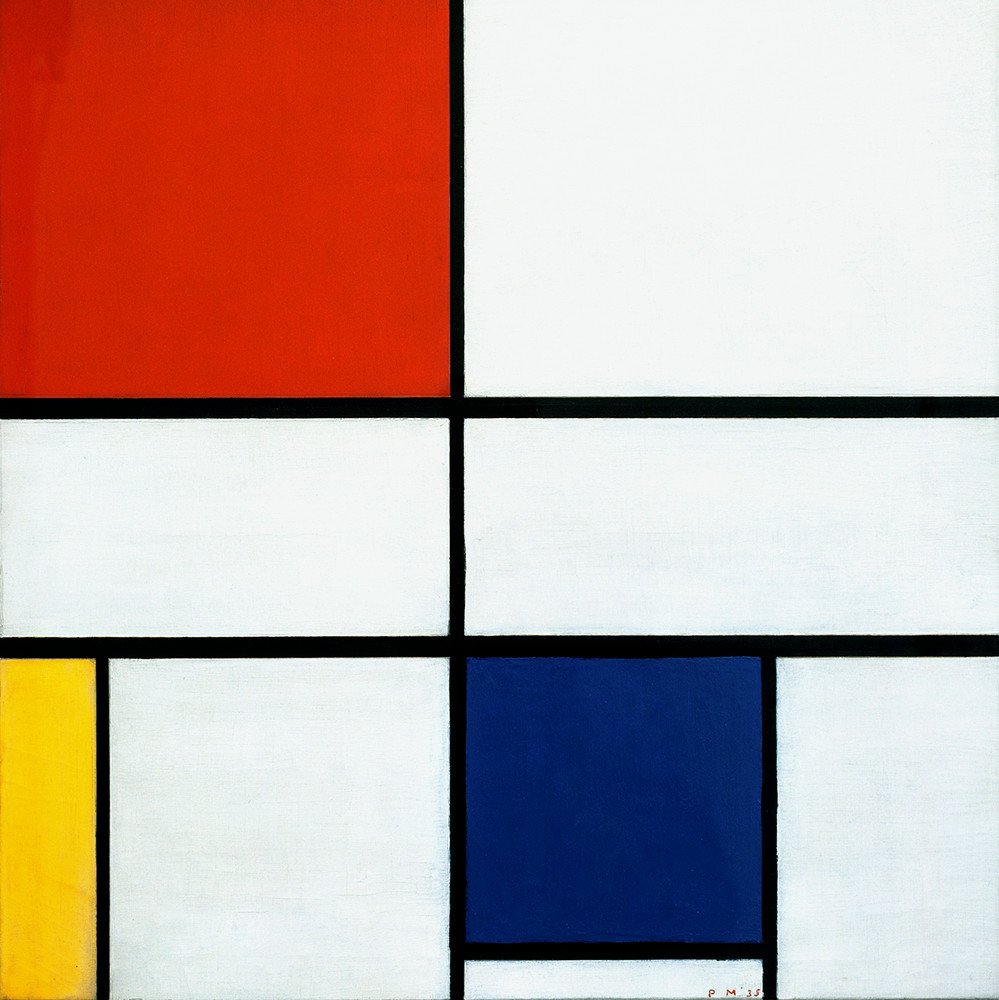

One of the best ways we have of defining complexity relies on how concisely we can describe an object. The more concisely we can describe something, the less information it contains, and the less information something contains, the less complex it is. This is called the Kolmogorov complexity. Consider the following paintings:

The Mondriaan can be described very efficiently: it consists of nothing but large blocks of a single color. If we know where these blocks are, and what their colors are, we can already reproduce the painting almost precisely. The Vermeer is trickier, but we have a lot of structure to work with. To begin with, some colors occur more than others, so we can give frequent colors shorter codes. The painting contains many gentle, smooth curves, and patches of almost uniform color. If we go deeper, we could even use a model of human anatomy, and describe the painting as an image of a girl pouring milk. We could even model the way light bounces of a finely plastered wall, or the way cloth drapes off a woman’s hips. In theory, all this knowledge could help us to describe the painting efficiently. Pollock did not make things so easy for us. To describe his painting, we have no recourse but to say for each blob of paint exactly where it landed, what shape it took, and what its color was.

Thus, going by the Kolmogorov complexity, the Pollock is the most rich in information, followed by the Vermeer, with the Mondriaan containing the least. But which one feels the most rich in information to us? If we forget about the historical context temporarily, the Vermeer clearly represents the kind of image that seems the most rich to us. Technically, the Pollock contains more information, but it’s not information that we can do a lot with.

Sophistication is a proposed method to deal with this problem: an approach that hopes to count only the structural information in an object. It attempts to do so by storing the object in a two-part code. It first stores a model, and then an input to that model, so that the two parts are sufficient to reconstruct the objects. In the example of the paintings, both the Mondriaan ad the Pollock have very simple models: one which is only capable of drawing large colored rectangles, and one which paints only small blobs of paint. The input to the first is very small, we only need to specify a handful of colored rectangles. The input to the second is huge: for each blob of paint, we must specify the poisition, shape and color. This, we knew already: the descriptive complexity of the Mondriaan is small, and that of the Pollock is huge. But if we use two-part coding, they bothg have relatively small models.

Not so for the Vermeer: if we want to use every bit of structure possible to describe it, we can use all the patterns mentioned before: the way light behaves, the facial structure of a young woman, the way milk flows. All these structures become part of the model, in the two part description. So while the Vermeer’s total descriptive complexity is somewhere in between the Mondriaan and the Pollock, the amount of information in its model, is bigger than either two.

This, at least, is the idea that motivates sophistication. Many authors over the last three decades have attempted to formalize this intuition, with varying degrees of success. In this article, we take a critical point of view: the canonical objective two-part coding required for sophistication, cannot be made to work. There are always two-part representations with differently sized models. Which of these reaches the absolute shortest description is depends on arbitrary choices in the construction of the sophistication.

Our article does not prove that sophistication is fundamentally impossible, but it does find problems with every published proposal. We also provide two informal arguments to doubt that sophistication can be made to work. It is clear that if this idea is going to work as currently proposed a far more thorough approach is required.